The following is text and images from the December 1963 TRAINS magazine. Written by renowned editor David P. Morgan, the article provides a detailed history of the development of the Class J3 57 locomotive, of which Nashville’s Locomotive 576 is a member. For more information about plans to restore 576 to operation, visit our “Projects” page. Many thanks to Kalmbach Publishing Co. for permission to publish this article online.

Gliders, Yellow Jackets, and Stripes

A history of the N.C.&St.L. No. 576 and its peers

Adapted from a Trains Magazine Article written by David P. Morgan in 1963

Adapted from a Trains Magazine Article written by David P. Morgan in 1963

LET this be read into the record on behalf of the 20 locomotives of 4-8-4 wheel arrangement that comprised Class J3 of the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railway: they were, above all else, war engines. As much as the gaunt smoke-deflectored Decapods that roamed the Ruhr of the enemy or the G.I. 2-8-0’s that were barged to the beaches of Normandy in the summer of 1944. For gasoline, draftees, munitions, half-tracks, oil, troops, and all the other impedimenta of making war rode toward the front of 1942-1945 behind the round-bottom tanks of J3’s; and but for those J 3’s, a railroad line of curves, grades, single track, and too many trains would have snapped and placed many an overseas military campaign in jeopardy. In a sense, of course, all of the 42,700 locomotives that propelled American railroading through the conflict were war engines without whose cumulative tractive effort logistics would have been meaningless. But most of these engines were tired, at least one world war too old to cope with the size and speed of the load imposed by global warfare. They embarrassed green firemen, exhausted the patience of boilermakers, and made old men of young dispatchers. The true war engines, the ones that held the line figuratively and literally, were the modern power that burned anything a stoker screw could digest, stayed out of the shops, ran varnish as fast as the timecard 01′ the hogger’s nerves allowed, and pulled everything for which the yardmaster could locate waybills. Engines such as the NC’s J3’s.

You may not be familiar with them. Few are, outside the South. So desperately were they needed to keep the railway fluid in the war that they went into service immediately upon de-livery without any speechmaking or breaking of the grape over the pilot beam. Alco advertising aside, the trade press ran not a line on the J3’s, and it remained for reader Cpl. Robert W. Richardson to call them to the attention of the editors of TRAINS. In the two decades since, the only amends of any note were made by H. G. Monroe in a couple of Railroad Magazine articles. But then, for every Patton there were a million unsung, expendable soldiers, and so it was with the J3’s. Their service record, unadorned by adjectives, lives on in the company’s annual reports which show that the road, in 1943, more than doubled its 1940 ton-mile production and quadrupled its prewar passenger business. Only a remarkable weapon could have supported such a war effort, and like many remarkable weapons, the J3 was germinated years before the war.

“…That’s a Stripe for you. They loved to roll…they went barking over Coon Mountain with tonnage without so much as a quarter slip of their big 70-inch wheels, they ‘ate up’ hot postwar schedules like the City of Memphis. They went to war and they came home on the winning side.”

As the Alco ad stated (“A Good Design in 1930 Further Improved in 1942” ), the J3’s were lineal descendants of earlier 4-8-4’s. On the brink of the depression the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis – with the blessing of 71-per-cent-owner Louisville & Nashville – went shopping for new engines for the first time in five years. At that time the 1203-mile road’s newest, most successful, and heaviest (except for three old Mallet pushers) power was a dozen J1 Mountain types, built to a odified light U.S.R.A. 4-8-2 design by Alco and Baldwin in 1919, 1922, and 1925. They could lift 1900 tons on a 1 per cent grade, which approximated the fast freight rating of NC’s biggest Mikes, yet their 69-inch drivers enabled them to average 36 mph across the mountains with 10- to 13-car Dixie Route limiteds. Indeed, these 4-8-2’s were the first engines the railway acquired that were truly tailored to its peculiar physical and traffic characteristics.

NC (or N&C as its employees always referred to NC&StL in a throwback to its ancestral Nashville & Chattanooga, chartered in 1845) ran its mainline iron from Memphis and Paducah, Ky., across to Nashville and Chattanooga, and by lease of the stateowned Western & Atlantic, down into Atlanta, thus connecting gateways on the Mississippi, Ohio, Cumberland, and Tennessee rivers with the distribution center of the South. Approximately half of its tonnage was overhead and subject to competition with other lines, most of which had shorter routes. Between Nashville and Atlanta NC was a strategic link in the Chicago-Florida Dixie Route, which was far and away the most popular choice to the beaches until after World War II. As late as 1930 passengers contributed 20 cents of every NC revenue dollar.

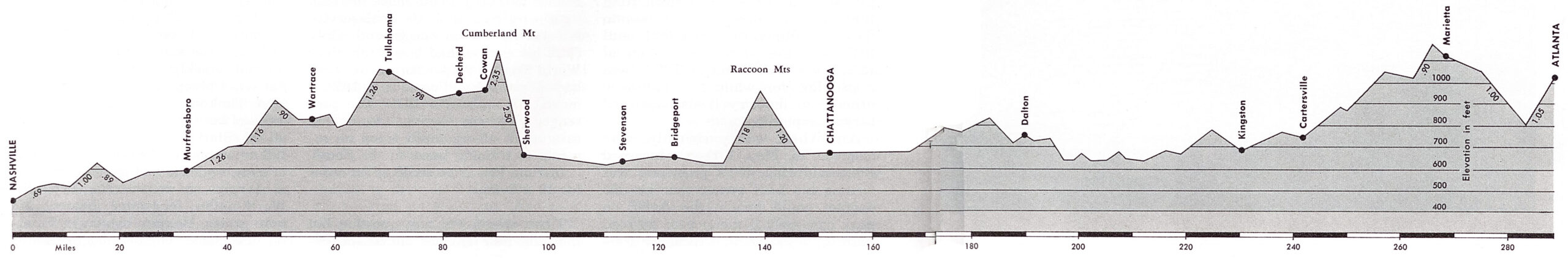

All of this competitive traffic had to funnel through the Chattanooga Division: 151.7 almost tangentless miles between Nashville and Chattanooga with a 1.5 per cent ruling grade over Raccoon Mountain and a 2.5 per cent helper grade over Cumberland Mountain. Which is to say, NC required locomotives which could work freight and passenger trains interchangeably, make time, and keep their feet in the mountains [see track profile below].

To improve upon the J1 4-8-2, newly promoted Superintendent of Machinery C. M. Darden and his staff centered their efforts upon a marginally larger but much free-steaming boiler. Use of a four-wheel Delta trailing truck increased grate area and improved combustion and combustion chamber design, and incidentally dictated a 4-8-4 wheel arrangement. The 70-inch wheel was frankly a compromise between the opposing demands of Raccoon Mountain tonnage ratings and the Dixie Flyer’s schedule. And as compared with a J1, a boost in pressure from 200 to 250 pounds permitted a reduction in cylinder diameter from 27 to 25 inches. What came off the drawing boards onto blueprint paper looked very much like what would have resulted if the U.S.R.A. had sponsored a light or 4-8-4-A design.

If the South’s first 4-8-4’s were conservatively proportioned because of NC’s clearances, bridges, and 90-foot tables, then its design was complemented by unusual and imaginative attention to the smallest component.

Lateral-motion driving boxes were applied to the first and second, or main, driving axles to ease the J2’s through NC’s uncountable 6-degree curves. The long-travel Walschaerts valve motion (operated by an inverted power reverse gear), selected for its economy of steam, was so expertly laid out that Alco’s engineers could find naught to change or improve upon in terms of steam events, cutoff, lead, and lap. Every modern auxiliary to improve steaming or operation – syphons, feedwater heater, Type E superheater, front-end throttle, an Alco patent outside-bearing engine truck was added except a booster, which NC rejected after tests with Mikes had indicated that it robbed the boiler of steam at the moment of its peak steam demand.

But Darden’s greatest satisfaction was derived from the J2’s one- piece cast-steel engine frame beds. A costconscious management agreed to spend $12,000 more per engine on the one-piece frames with integral cylinders in order to eliminate the fractures and bolt adjustments which were plaguing the built-up frames of larger four- and five-coupled engines. And Darden went one step further by adding brackets to the boiler supports of the cast-steel frame beds. These brackets, in turn, carried all the external piping which would otherwise have been affixed to the boiler itself with studs. Darden believed that a boiler should be just that, a steam generator – not a wall to tack on everything including the kitchen sink. A J2 boiler expands as much as 1.5 inches when under steam, and stud-supported piping causes leaks and weak pipe connections.

Only days before the stock market crash in October 1929 the railway placed an order with the American Locomotive Company for five J2 4-8-4’s, Nos. 565-569, and the finished engines left Schenectady for Nashville in February 1930. At that time the wheel arrangement had not acquired a universally accepted popular name; instead, 4-8-4’s of the period were variously dubbed Northerns (NP), Confederations (CN), and Poconos (DL&W). Accordingly, the NC titled its J2’s the Dixie type.

THE new Dixies were, with mild qualifications, handsome engines. They looked like a condensed C&NW H or rather U.S.R.A.-ish or typically NC, depending upon your orientation. In point of size they were the smallest U.S. 4- 8-4’s ever built, almost identical in engine weight to Canadian National’s rapidly expanding roster of 6100’s and actually outweighed by Mopac and Pennsy 4-8-2’s. In appearance they looked large enough, handicapped solely by a smallish cab and the 16-ton, 10,000-gallon Vanderbilt tanks required by NC’s turntables. Certainly the Dixies loomed large in the lens of the company photographer as they came past Lookout Mountain on the point of the Dixie Flyer or, just for laughs, posed haughtily beside the war veteran General.

Though Dixies they may have been to the front office, “Gliders” they immediately became to their jealous crews. The J2’s simply slid into curves, thanks to their lateral motion boxes. No bucking, no pounding. And shuttling back and forth between Nashville and Chattanooga on a first-in, first-out basis, working freight and passenger runs with impunity, the engines were a revelation in utilization. Especially to the employee on the coal chute at Cowan, Tenn., who fueled them in both directions at the foot of Cumberland Mountain. When the Dixies were new he asked Mr . Darden how many J2’s the company owned. Informed that the class comprised five engines he said, “You must be mistaken. I’ve had fifteen of ’em go through here today.”

The J2’s were everything that the railway had expected, but they were to acquire no new sisters for a dozen years. Whereas the NC had paid 7 per cent dividends on its stock from 1916 until the depression, it was in the red continuously from 1931 until 1937 with the solitary exception of 1936. Even the advent of T.V.A. was a paradox, for while the Authority ushered in industry it also spawned barge competition.

| CATEGORY | NC&StL J1C class 4-8-2 |

NC&StL J2 class 4-8-4 |

NC&StL J3 class 4-8-4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cylinders, in. | 27 x 30 | 25 x 30 | 25 x 30 |

| Drivers, in. | 69 | 70 | 70 |

| Boiler Pressure, lbs. | 200 | 250 | 250 |

| Grate area, Sq. ft. | 70.3 | 77.3 | 77.3 |

| Weight on drivers, lbs. | 224,000 | 220,000 | 228,000 |

| Engine weight, lbs. | 340,000 | 381,000 | 400,500 |

| Engine & tender, lbs. | 515,000 | 575,000 | 685,500 |

| Heating surface, Sq. ft. | 4,039 | 4,193 | 4,203 |

| Superheater, Sq. ft. | 1,080 | 1,782 | 1,782 |

| Tractive effort, lbs. | 64,800 | 57,000 | 57,000 |

| Builder | Baldwin | Alco | Alco |

| Date | 1925 | 1930 | 1942-1943 |

And then, quite abruptly, war loomed. In May 1941 a concerned Fitzgerald Hall, NC’s president, was writing his L&N owner that his 195 engines could handle the traffic on peak days only if there were no road failures, work trains, wrecks, or traffic interruptions; and that he urgently needed authority to purchase 10 diesel yard engines and 10 dual-service 4-8-4’s. He was on safe ground. Only 30 of his engines had been built since World War 1. And whereas the road had moved 5.4 million tons in 1939, it moved 8.6 million in 1941. The passenger load was soaring, too, mainly as a result of organized troop movements to training bases in the South. In June 1941 Alco received an order for 10 4-8-4’s.

THERE was never any question but that the new engines should be essentially duplicates of the 1930 Dixies. The J2 was a known quality. All she needed in the J3 revision was to take advantage of the technology which had occurred since 1930. Darden and his staff quickly upgraded their original 4-8-4 blueprints. First, they specified Timken roller bearings for all axles of both engine and tender. Next, all auxiliaries and components took full advantage of the best of the builder’s art, regardless of initial cost (e.g., multiple-valve throttle, Type SA Worthington feedwater heater, pin hole grates, Boxpok drivers).

Finally, the same engineering freshness that had won the Gliders such an excellent reputation was lavished upon their successors. Not only was all piping mounted on frame boiler supports but the power reverse gear, too, was mounted on the valve motion frame-not hung on the boiler. Again, the air brake stand in the cab was supported on a frame pedestal-not hung on the boiler. Superheated steam was supplied to such auxiliaries as the air compressor (“They told us it couldn’t

be done,” Darden recalls, “but it was just a matter of using the proper additive oil to lubricate the pump. After all, what better place to use superheated steam than on a cross-compound pump?”). The drivers were counterbalanced with painstaking care.

All the while, the front office worried over what its first new engines in 12 years should look like. President Hall felt that the NC “should ‘doll’ the new engines up so as to make them look modern,” and he was agreeably impressed by an all- streamlined proposal which Alco furnished (apparently a design similar to N&W’s J). However, owner L&N thought that the $6,250 which such a jacket would cost per engine was excessive and suggested that NC streamline the 4-8-4’s in its own shops, much as the two roads had done with some older Pacifics modernized for Dixie Flagler service in 1940 at a cost of only $1500 per engine. Sorrowfully, Hall contemplated the NC’s effort-Pacific 536 – and wrote, “I have been rather disappointed in our own efforts to fix up an old locomotive for this service.” So what the NC settled for was a semistreamlined ( “streamstyled” was the term used in those days) look.

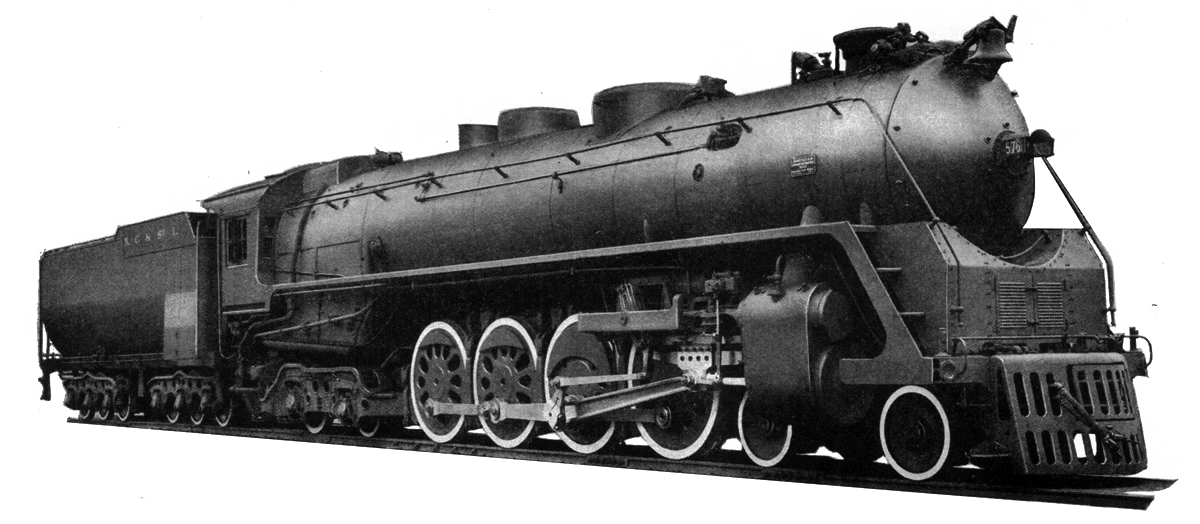

As delivered in July and August of 1942, Nos. 570-579 (including Nashville’s own 576) of class J3 bore a smoke box-diameter bullet nose as the cap on a pipe-free, completely jacketed smokebox and boiler. A broad yellow skirt extended up the steps from the pilot beam and along the running board to the cab, thence across the flanks of the J3’s 16-ton, 15,000-gallon semi-Vanderbilt tender. “Yellow Jackets” their crews nicknamed ’em, and the name stuck.

ANY name would have been a term of endearment, for the J3’s were, right from the start, superb locomotives. ”

How fast will those Yellow Jackets roll?” an engineer asked Mr. Darden not long after they were delivered.

“Well, now, you’re the engineer,” Darden countered. “How fast will they go?”

“I’ve held ’em open as long as I had the nerve, but they just keep going up,” was the reply.

How fast? Well, Murfreesboro is 31.7 miles out of Nashville, the last stop for the inbound Dixie Flyer, and the Yellow Jackets used to run that off in 30 minutes, even 28 minutes, start to stop. On occasion a J3 was given the rein up to 90 mph, and at least one hit 110 mph (which, interestingly enough, is the authenticated speed record attained by N&W’s J , also a 4-8-4 with a 70-inch wheel) .

They rode not only well at speed but easily. “Only engine I ever rode that was so quiet you could hear the wheel clicks of the trailing truck from the cab,” is the way W. A. Gaines puts it. He was the NC mechanical department man picked to restore the General to steam in 1962 and as sound a source of opinion on the railway’s power – 4-4-0 or 4-8-4 or even F3 -as you can track down. He remembers how well they steamed, that they could be hand crossfired into town in the unlikely event that their dependable Standard stoker quit, that the grate was so large you didn’t bank your fire but carried just a thin layer of coal and that you yelled to the fire cleaners at Cowan, “Don’t touch that fire, don’t clean it – I’m going on through!”

Or ask Darden. “They threw into oblivion all of our shopping schedules,” he says. They ran from annual inspection to annual inspection without overhaul, required flues only after five years, and extended tire mileage to 100,000 miles from the 20,000 to 40,000 miles which NC had previously obtained. On the first 10 J3’s the railway only looked at two roller-bearing assemblies in 10 years’ time, and then just because tiny sand holes in the original frame castings finally let the oil leak out.

So they went to work, first between Nashville and Chattanooga, then on into Atlanta as 90-foot turntables were installed at all three terminals. Back and forth they went, piling up 11,000 miles a month on a short-haul, mountain-climbing, crooked piece of railroad. For instance, a J3 would depart Nashville at 10: 40 a.m. on No. 95, the Dixie Flyer’; arrive Atlanta, 288.3 miles distant, at 7: 40 p.m.; be turned and serviced in less than 2 hours; then leave again at 9: 30 p.m. on No.4; and be back in Nashville at 6: 40 a.m.

Within two months of their delivery Fitzgerald Hall was asking for more engines. At first he thought of asking for three two-unit 4000 h.p. E6-model EMD passenger diesels such as parent L&N owned, plus seven 4-8-4’s (the diesels would have worked L&N NC& StL trains Evansville-Atlanta), but the War Production Board wasn’t relaxing its ban on passenger power construction, so he had to settle for 10 more J3’s. NC toyed with the idea of adding high-speed Type E Franklin boosters to the newcomers at $12,000 each, also with specifying 25-ton, 22,000-gallon tanks. Ultimately, the boosters were nixed, as were the larger tenders (which would have required new turntables all over again). The 10 J3’s which Alco delivered in the fall of 1943, Nos. 580-589, were duplicates of the 570’s except for their cast-iron bells (brass had gone to war) and their lack of skirting (what was left was just a striped running board, which promptly earned them the nickname “Stripes” ).

IN the final analysis, the critique of the J3’s is this: they kept the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis fluid when by every index of even such a flexible transport as railroading, the company should have collapsed. Just look. NC canied fewer than 500,000 passengers in 1939 but more than 800,000 in 1941- then 1.6 million in 1942 and 2.6 million in 1943! Or consider ton -miles: just over 1 billion in 1939, 2.1 billion in 1942, and more than 2.7 billion in both 1943 and 1944.

Nor do the statistics by themselves do the railway or the J3’s justice. As Fred Whittemore, retired vice-president of operations, put it, “We dedicated ourselves to exertion of an allout effort … regardless of circumstanc’e or cost.” Oil, for instance. When German submarines chased coastal tankers out of the Gulf and the Atlantic, symbol oil trains took their place. During 1942-1943 NC ran an average of 6 to 8 oil trains from Memphis to Atlanta daily , with each of the 45-car specials running on a 19-hour schedule for the 5261h -mile run. Frequently these tank-car trains, loaded with oil and gasoline, were handled through terminals simultaneously with trains of ammunition and explosives. Again, during the period of J anuary 1, 1942, to November 30, 1944, the railway operated 3002 troop trains with 889,130 men aboard and hauled another 242,853 military personnel in special cars coupled to scheduled trains. And once NC deliver ed the entire

4th Armored Division to Camp Forrest at Tullahoma, Tenn., from Nashville – 64 trains’ worth of it then went back after training was completed and moved the 4th out, this time to Memphis (en route to Mojave, Calif.).

The J3’s survived the stress with but minor alterations. First, their grilled Commonwealth pilots, with horizontal swing retractable couplers, proved more esthetic than practical ; firemen and brakemen couldn’t agree on whose job it was to extract the reluctant drawbar. So gradually these were removed in favor of a simpler cast steel pilot with exposed coupler. Second, to pull a bullet nose off for a monthly smokebox inspection the roundhouse crew had to pull an engine outside the house and procure a mobile crane. So, one by one, the bullet noses were replaced by small headlight cones and, on at least two J3’s [including 576], by conventional smokebox fronts.

If the war had continued, the J3’s would certainly have been duplicated once again. In November 1943 Fitzgerald Hall wrote that if the conflict lasted two more years, NC should buy road diesels if available, or five more 4-8-4’s if not.

WAR did not last, however, and NC revenues began easing in 1945, and an operating ratio which had hung in the low 60’s during the early 1940’s suddenly soared to 93.6 percent in 1945, 96.9 percent in 1946, and 83.7 percent in 1947. All things being equal, of course, owner L&N would have preferred that its corporate child stick with steam. L&N was a coal hauler and had itself bought diesel switchers only to pacify civic anti-smoke committees and passenger diesels to resolve certain axleloading problems on Gulf Coast trestles. Yet all things were not equal. More a competitive bridge line than a coal road (“Our existence was dependent on speed and connections,” says Darden), NC possessed no particular traffic affinity for steam. Moreover, the railway had only 25 modern steam engines to its name and was therefore faced with the issue of replacing rather than supplementing.

In 1947 Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis ordered 21 1500 h.p. F3 cab and booster units from Electro-Motive, and the signatures on the order were the handwriting on the wall for the J3’s. From Nashville to Chattanooga three F3’s had a through southbound tonnage rating of 3600 tons vs. 1900 tons for a J2 or J3 4-8-4. From Chattanooga on into Atlanta the F3’s could tote 3975 tons vs. 2100 tons for a Dixie.

“WE didn’t owe them anything and they didn’t owe us any thing,” says Darden of the J3’s as they neared the inevitable torch. NC so cannily ran out the mileage on its roller-bearing Yellow Jackets and Stripes that by August 1952 President W. S. Hackworth was able to report that all of them were out of service, fully depreciated, worth $8867 each in scrap, and in need of repairs of $15,000 per engine. Owner L&N, busily dieselizing itself by that date, decided not to buy the engines, so they went to the cutting torch. All except No. 576. She was presented to the City of Nashville in 1953 and mounted behind a fence in Centennial Park – just a stone’s throw (or a whistle’s blast) from the former Nashville Shops of the railway.

The 576 behaved just like a J3 clear to the last inch of her journey to a permanent home in the park shade. The temporary spur into the park was laid on a grade and included a curve that was more like 30 degrees than anything the J3 had been designed to negotiate. Yet when a diesel yard engine got behind her, the 576 walked right around the curve. “Those lateral

motion boxes,” Mr. Darden says smiling.

But on the downgrade the 4-8-4 began to run, dragging the protesting yard diesel behind h er until she hit the level. “Those fine roller bearings,” says Mr. Darden. Well, that’s a Stripe for you. They loved to roll, they didn’t jar your kidneys out of shape on the curves, they went barking over Coon Mountain with tonnage without so much as a quarter slip of their big 70-inch wheels, they “ate up” hot postwar schedules like the City of Memphis. They went to war and they came home on the winning side.